Descendants of Holocaust victims are in a race against time to preserve oral histories and artifacts before the last survivors are gone.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., is collecting family heirlooms and stories from people around the world, such as Alli Allen of Atlanta.

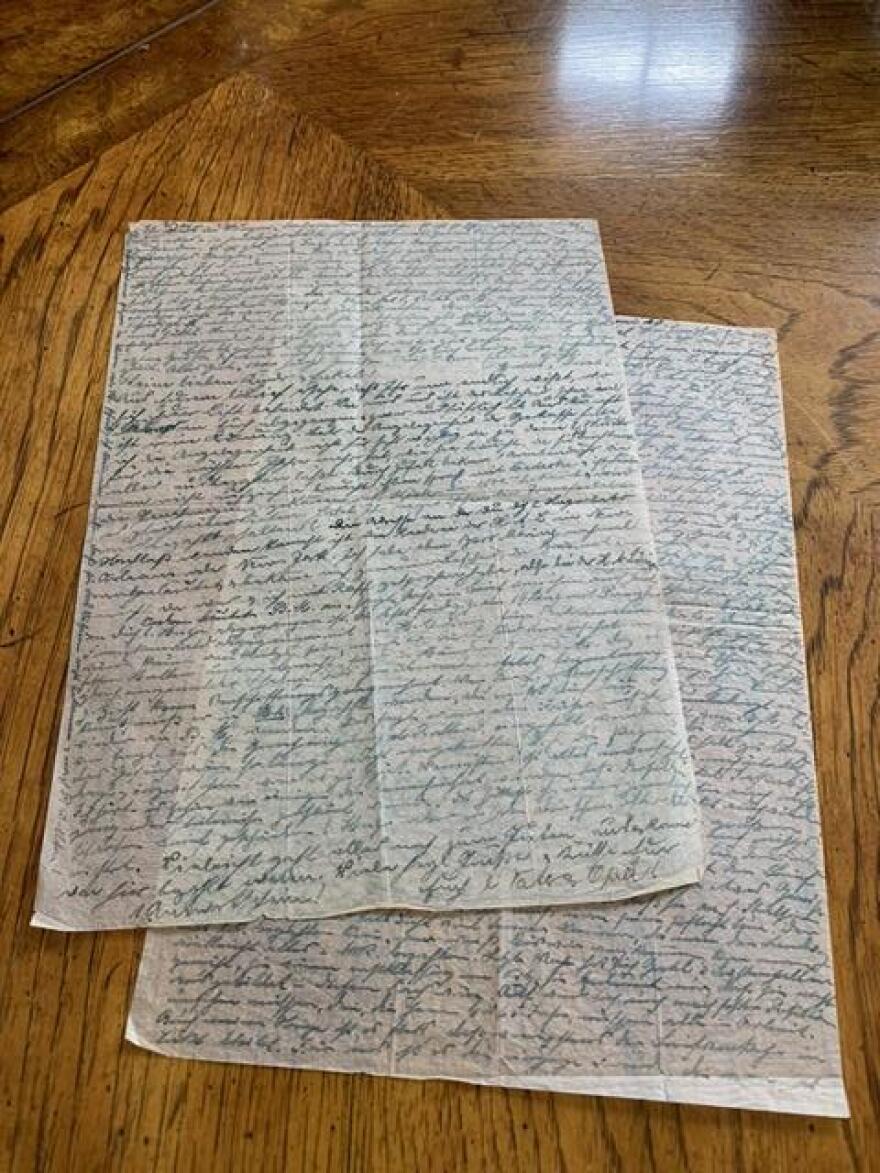

Allen is donating hundreds of letters sent between her great-grandparents Blanka and Max Hartstein in Germany and her grandparents Paula Hartstein Marx and Hugh Marx, who’d fled to the United States in 1938, just one week before Kristallnacht, the “Night of Broken Glass.”

On Nov. 9 and Nov. 10, 1938, Nazis burned and vandalized thousands of Jewish homes, synagogues and businesses and killed nearly 100 Jews. In the wake of that night, 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and sent to concentration camps.

The Nazi terror and genocide of millions of European Jews would continue until the end of World War II in 1945. It was the backdrop of hundreds of emotional letters between the Hartsteins in Germany and the Marxes in the United States.

Krya Schuster, curator at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, is overseeing the museum’s preservation of the collection.

Alli Allen: My grandparents lived in Stuttgart, Germany. My grandparents, along with my mom and uncle, who were 9 and 5 at the time, left in the middle of the night without saying goodbye to my great-grandparents. Right after they settled in Little Rock, [Arkansas] they started receiving letters from my great-grandparents. And these letters comprise a chronicle of my great-grandparents' demise.

My grandfather was constantly communicating with Germany. My grandmother, on the other hand, never said a word about the Holocaust because, as I later found out, she was unable to get her parents and her sister and other relatives out of Germany and she lived with the guilt of that her entire life.

After my grandmother died in 1999, my mom went up into her attic one day and found a box. And when she opened it up, it was full of hundreds of letters from my great-grandparents to my grandparents, and they were all written on onionskin paper in old German script. They are very difficult to read because I know the ultimate outcome.

Here's an excerpt of one that was written by my great-grandmother Blanka Hartstein to my grandmother Paula Marx right after my grandparents arrived in the United States:

You're in the process of taking the most important step of your lives this far. God has truly blessed you with his favors and let you lay down your life’s path. These are my daily and hourly thoughts. Even if we ourselves are near the frustration point, since everything seems to come toppling down on top of us. But now, my loved ones, do not look back. Draw a thick line. Start your new lives unburdened in good health and with renewed courage. If I will be able to hear your voices just one more time, maybe for the last time, I will forever ingrain them deep in my heart.

Alli Allen: And then just a short six months later, on May 8, 1939, my great-grandmother wrote to my grandmother:

We sit here on a powder keg the entire time. What shall happen to us? The ones who have passed on no longer have these worries, but one would have certainly wished to have a different conclusion to one's life.

Alli Allen: My great grandparents were murdered, ultimately, in Auschwitz on July 31, 1944.

Kyra Schuster: When I hear Alli read these incredibly poignant words of her grandmother and great-grandmother, it's very touching. It's very moving.

I have hindsight. I know what happened to this family. I already know what their fate is. But when you're reading the words as they're being experienced and as they're written, it really gives you a unique personal perspective of what they were going through.

Every letter is unique. Every family's experiences are different. So the fact that her grandmother saved all of this is absolutely tremendous. And I think it'll be an incredible resource for future scholars and researchers to really get a sense of what it might have been like for somebody to have experienced this firsthand.

Alli Allen: It's evident from the letters how close my grandmother was to her parents. And I know that my mom and uncle were very, very close to their grandparents, who used to walk them to school every day. And I just think the pain of their failure to be able to get my great-grandparents out was just overwhelming.

Kyra Schuster: I also talk to a lot of survivors and veterans who have never recorded their story before because they don't want to talk to their family. It's too emotionally traumatic to relive this with a family member. But they'll talk to me or they'll talk to my colleagues because we're an impartial third party who know what questions to ask.

The Holocaust was such a complicated event in our history, both physically and mentally. It's not something that's easy to wrap your head around. Millions and millions of people were murdered. And how do you educate people about that? How do you have other people wrap their heads around that? How do you make a personal connection to that?

We do it by documenting. We do it by preserving the physical materials. We do it by sharing the stories of not only the survivors and the veterans, but those that we lost; but also from perpetrators and bystanders and witnesses. They're part of the story, too.

I think of our collection as a puzzle that has no border to it. It’s like a jigsaw puzzle, right? When we put all of those puzzle pieces together, it really helps us form a larger picture and also adds to our understanding and education.

Alli Allen: My mom and my uncle worked extremely hard on this collection, getting everything translated and binding it into books for our family. And it is, in my opinion, the one positive thing — if there is something positive that can come out of the Holocaust — that it now will be available to help educate people and provide hope that nothing like the tragedy of the Holocaust will ever happen again.

Copyright 2021 Georgia Public Broadcasting